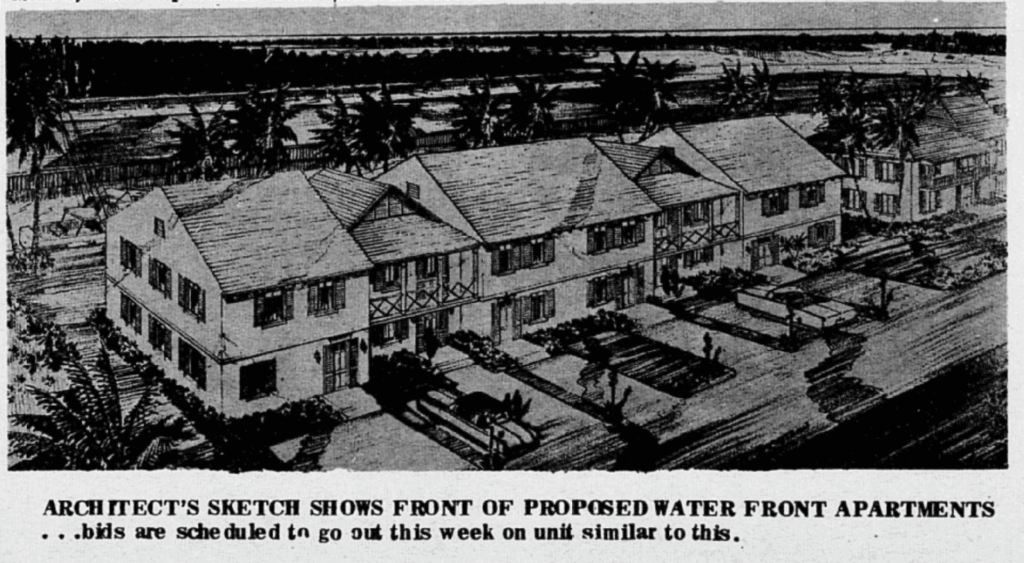

In 1963, Boynton Beach entered a new era of residential growth when former mayor J. Willard “Bill” Pipes announced plans for a $3.5 million condominium complex to be built along the west side of the Lake Worth Lagoon between Northeast 10th and 12th Avenues. The project, called Park Shores Manor, was planned as a 23-building community of two-story residences, totaling 117 living units. It represented one of Boynton Beach’s first ventures into the townhouse and condominium style of living, a concept still new to most of Florida at the time. Pipes, who had been a Pepsi-Cola executive before returning to local business, saw in Boynton Beach the ideal setting for a modern, self-contained residential community that combined independence with shared amenities.

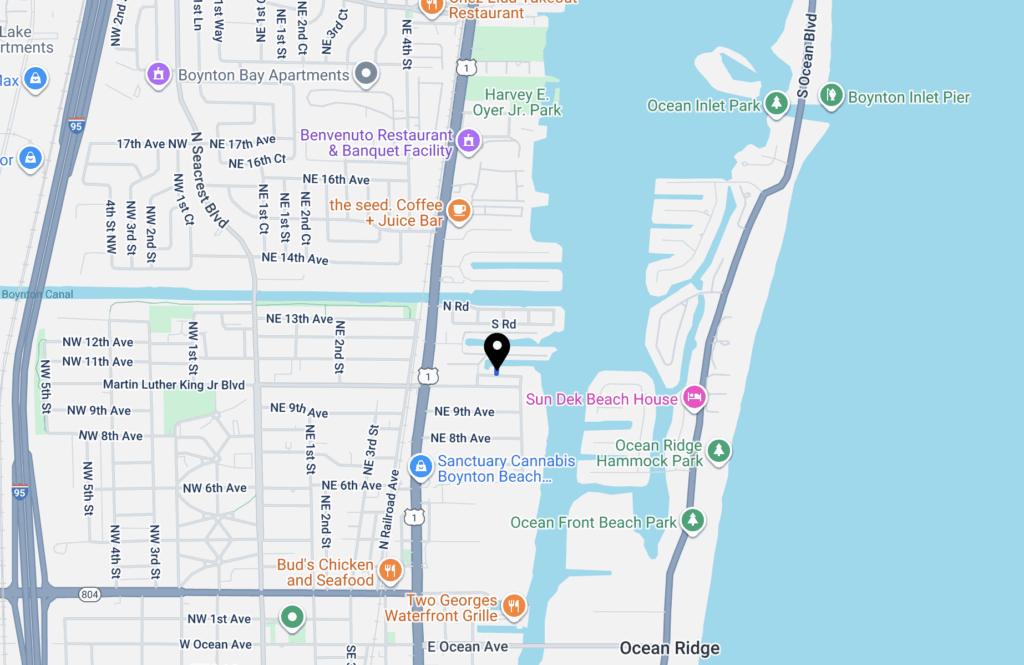

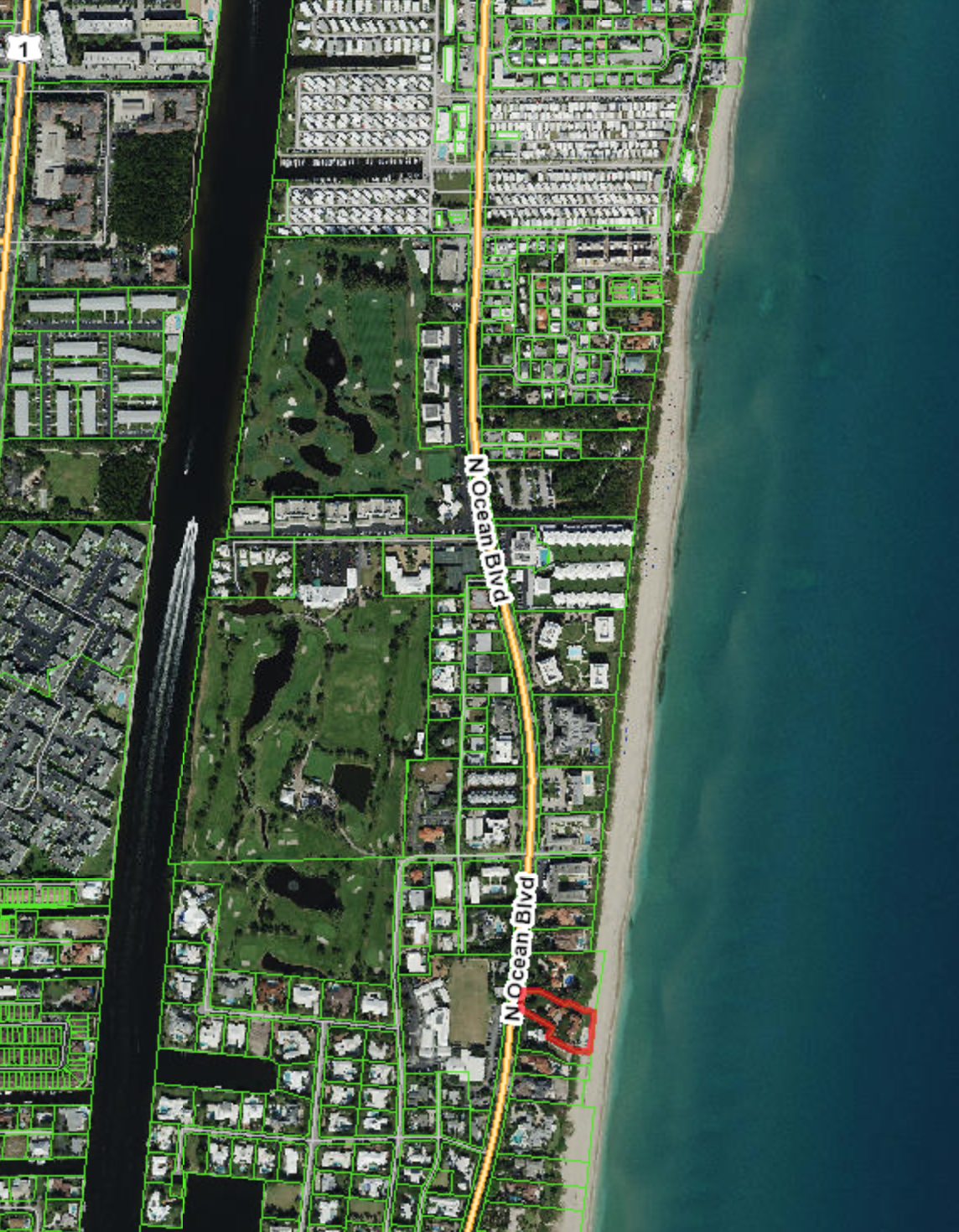

Palm Beach architect John Stetson designed the project in a “tropical, island-type” style with a Mediterranean influence. The homes were organized as townhouses with living rooms and kitchens on the first floor and bedrooms on the second. Each building faced either Lake Worth (today’s Intracoastal Waterway) or a man-made canal and included a private dock and patio. Walls and hedges separated the units, creating privacy while maintaining a sense of community. The four-acre property was located almost opposite the Boynton Inlet, offering quick access to the Intracoastal Waterway and the Atlantic Ocean.

Pipes emphasized that Park Shores Manor would be built as a true condominium, a legal arrangement that allowed each owner to hold title to their individual unit and the land beneath it. This differed from the cooperative housing model, where residents owned shares in a corporation rather than their own property. He explained that this structure gave owners the freedom to obtain mortgages, buy and sell their homes independently, and build personal equity. It was a new form of home ownership that fit the optimism of postwar Florida and the growing desire for maintenance-free living near the water.

The plans included a shared clubhouse, putting green, swimming pool, and shuffleboard area. Units were offered in one-, two-, and three-bedroom models priced from $14,000 to $24,000. Each home featured individual air conditioning and heating, built-in television aerials, and access to 75-foot-wide canals. The first building, containing six units, was projected to cost about $90,000, excluding land costs. Construction was expected to begin in mid-1963, and future phases would proceed according to sales. The Jay Willard Corporation, headed by Pipes, managed both construction and sales.

By early 1965, Park Shores Manor Town Houses had become a reality. A newspaper advertisement that January invited buyers to enjoy “carefree living” in a waterfront community. The ad described one- and two-bedroom townhouses with carpeted bedrooms, tiled baths, G.E. kitchens, and sliding glass doors. Each home had individually controlled heat and air conditioning, private boat dockage, and access to deep, dredged canals just off the Intracoastal Waterway. The community was only five minutes from Gulf Stream fishing grounds.

By early 1965, Park Shores Manor Town Houses had become a reality. A newspaper advertisement that January invited buyers to enjoy “carefree living” in a waterfront community. The ad described one- and two-bedroom townhouses with carpeted bedrooms, tiled baths, G.E. kitchens, and sliding glass doors. Each home had individually controlled heat and air conditioning, private boat dockage, and access to deep, dredged canals just off the Intracoastal Waterway. The community was only five minutes from Gulf Stream fishing grounds.

Presale prices ranged from $17,900 to $25,400, including the lot. Six homes were ready for immediate occupancy, with financing available for up to twenty years at six percent interest. Ownership included a one-year membership to the Cypress Creek Golf Club, and residents could join a private club and pool if they wished. The ad described a planned colony of 120 townhouses at 658 Manor Drive in Boynton Beach, offering an organized yet independent lifestyle along the water.

Park Shores Manor combined modern construction with coastal living. It offered residents the privacy of individual ownership with the comfort of shared amenities. The architecture, setting, and ownership model reflected Florida’s changing identity in the 1960s, when towns like Boynton Beach began transforming from quiet coastal communities into planned residential centers. Pipes and his team built more than a set of homes. They established one of Boynton Beach’s earliest examples of condominium-style living, setting a pattern for future developments that would define the region’s growth for decades.

Fun fact: Rider Road is named for Willard Pipes’ wife Jean Rider Pipes. Today the townhouses sell for $275-$400,000.

It’s a little piece of paradise; one that makes Boynton Beach so special.