INTRODUCTION

This research chronicles Florida’s notorious Ashley Gang and their connections to Boynton Beach. Readers will learn about John Ashley and his infamous bank-robbing posse that kept a secret hideout in western Boynton, held-up trains and interacted with unsuspecting Boynton residents.

In addition, we share the surprising revelation of a prominent Boynton pioneer family whose 16-year-old daughter married into the outlaw Mobley-Ashley family and some speculation of how Boynton locals supplied the gang with groceries and sundries—and one famous son who even lent Ashley his pistol!

1888

John Ashley is born near Fort Myers, Florida.

1896 – December

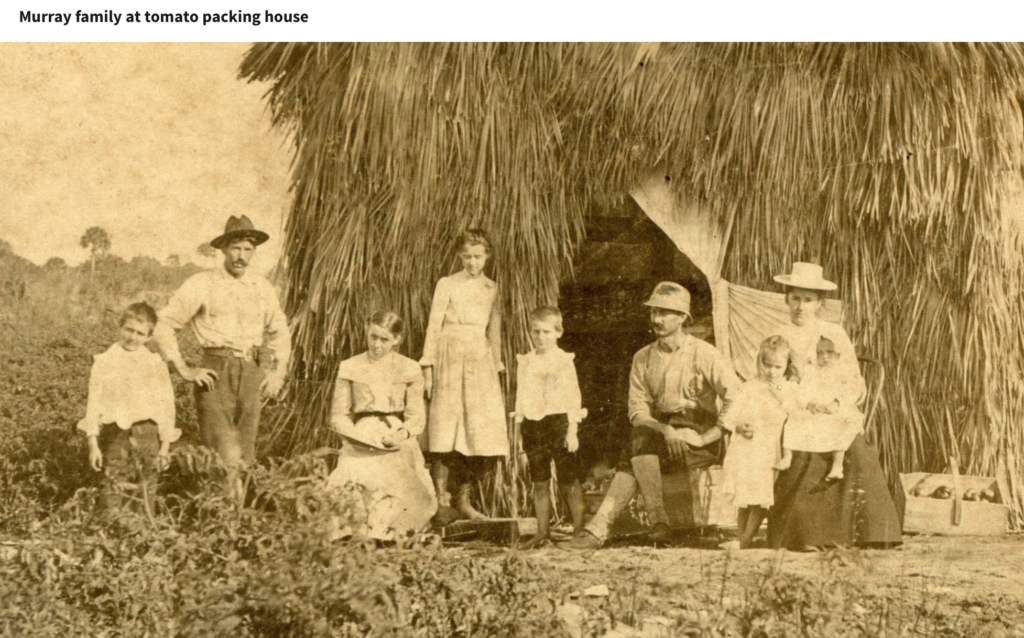

Horace Bentley Murray and his wife Mary Elizabeth Smith moved to Boynton from Michigan. Murray was a tomato farmer and crew leader/carpenter for Major Nathan S. Boynton’s oceanfront hotel.

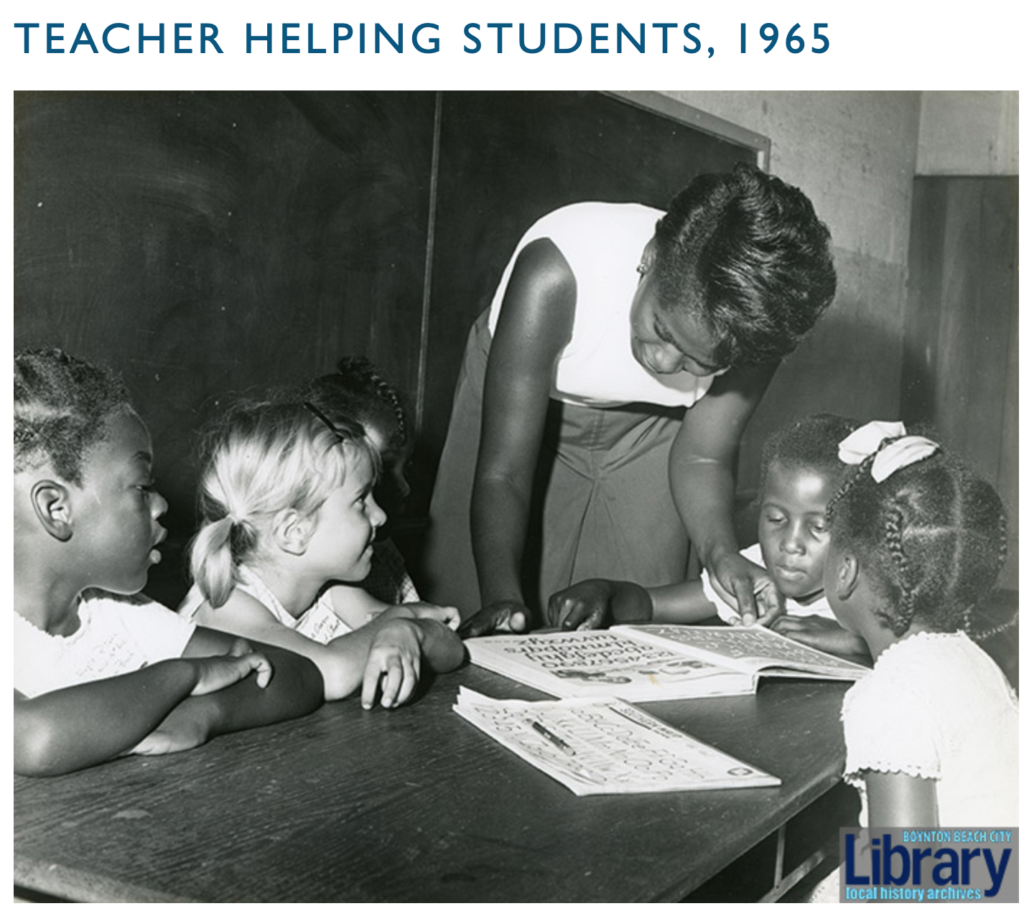

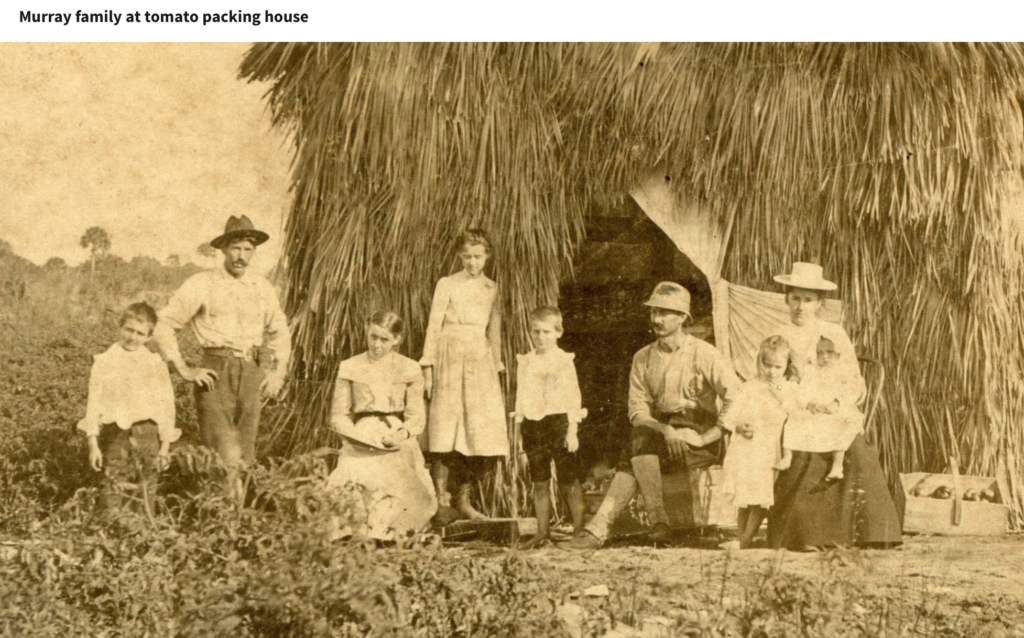

Horace Murray & wife Mary Smith Murray (far right), with William Henry “Uncle Billy” Smith to the left, along with Murray children and an unnamed Boynton schoolteacher (Boynton Beach Historical Society)

1898

Mary Smith Murray’s younger brother William Henry “Billy” Smith and his wife moved to Boynton and lived near the Murray family. Local historical accounts don’t mention much of Smith, but he is identified in a Murray family photo as “Uncle Billy.”

It was that photo that instigated the research which led to the Ashley Gang connection. In the photo, Billy appears rugged and self-confident, wearing a wide-brimmed hat and long-sleeved shirt while standing in front of the Murray’s palmetto frond packing shed. While you don’t see any visible guns in the photo, it’s likely that Smith was packing a pistol, as in the wilds of tropical Florida wildlife outnumbered humans, and gun ownership (revolvers and rifles) was very important. Billy Smith farmed and became Palm Beach County Supervisor of Roads. Mary Smith’s sister, Lillie, lived in Boynton her entire life, and married carpenter Charles Davies.

Billy Smith and wife Florence had four daughters; it was teenaged Dorothy Louise (born in 1913) who married into the Mobley-Ashley family at age 15— Louise’s daughter, Mary Lou Mobley, child of the notorious Lubby Mobley was born two months later. John Robert “Lubby” Mobley was born to gang members George Westley “West” Mobley and Mary Alice Ashley (John Ashley’s sister). Lubby lived a crime-riddled gangster life both before and after his 1928 marriage to Dorothy Smith.

1911 – December

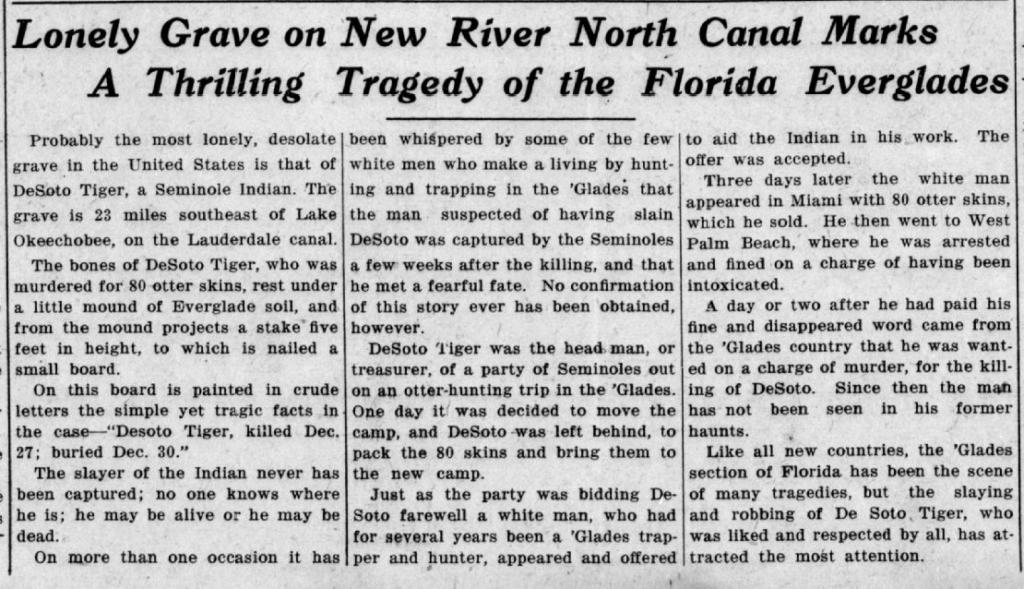

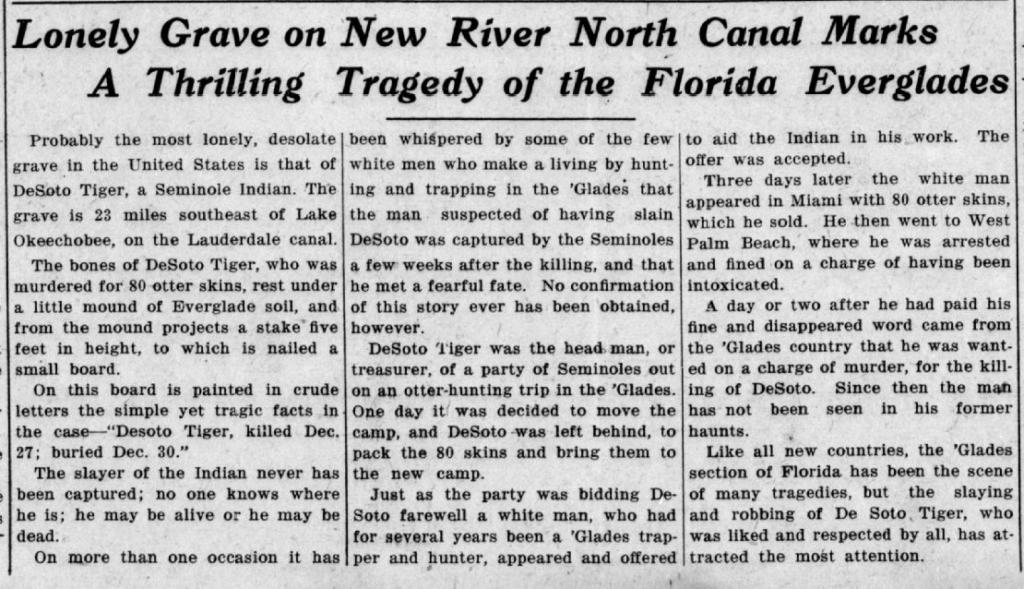

JOHN ASHLEY ACCUSED OF MURDERING FELLOW TRAPPER DESOTO TIGER

DeSoto Tiger’s Gravesite (9 Oct 1913, Lake Worth Herald)

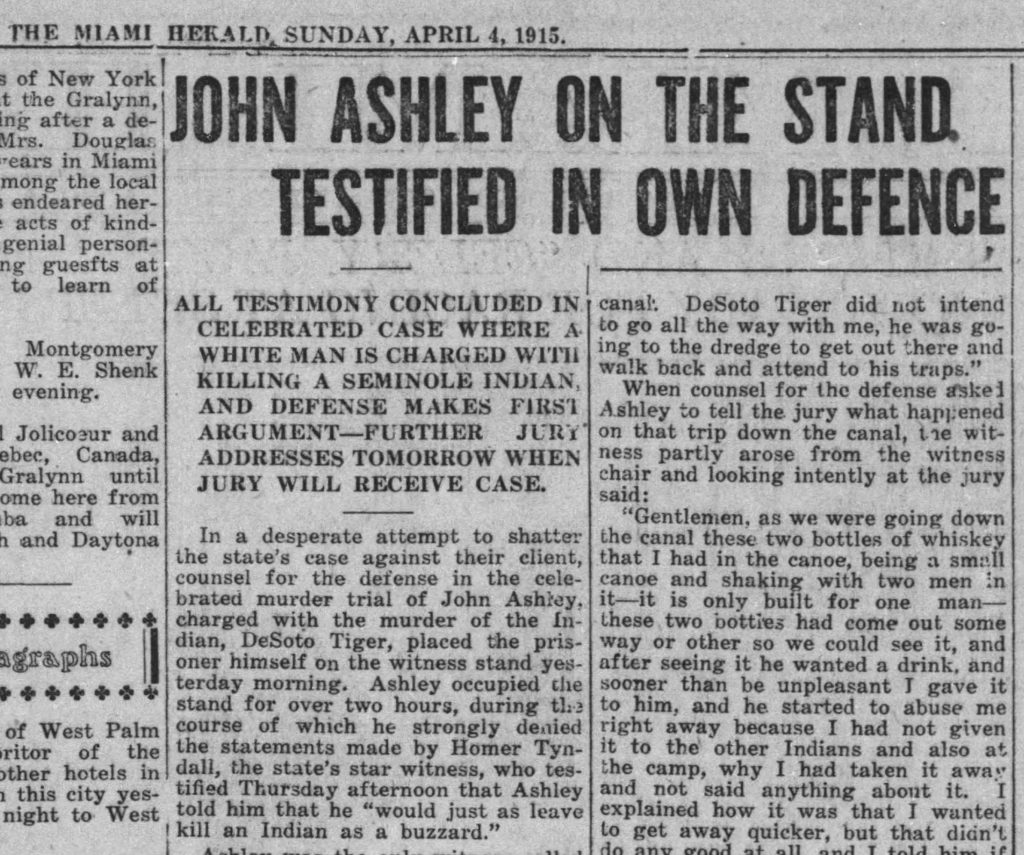

The Boynton story begins shortly after 19-year-old trapper John Ashley was wanted for the December 1911 murder of DeSoto Tiger, son of Cow Creek chief Tommy Tiger. Ashley was the last person seen in a canoe with DeSoto and was spotted selling a load of valuable otter skins. Later, in 1915, Ashley would testify on his own behalf and claim self-defense in Tiger’s killing.

A charming John Ashley testifies on his own defense saying that the DeSoto Tiger shooting was self-defense (4 April 1915, The Miami Herald)

1910-1912

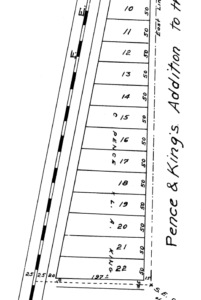

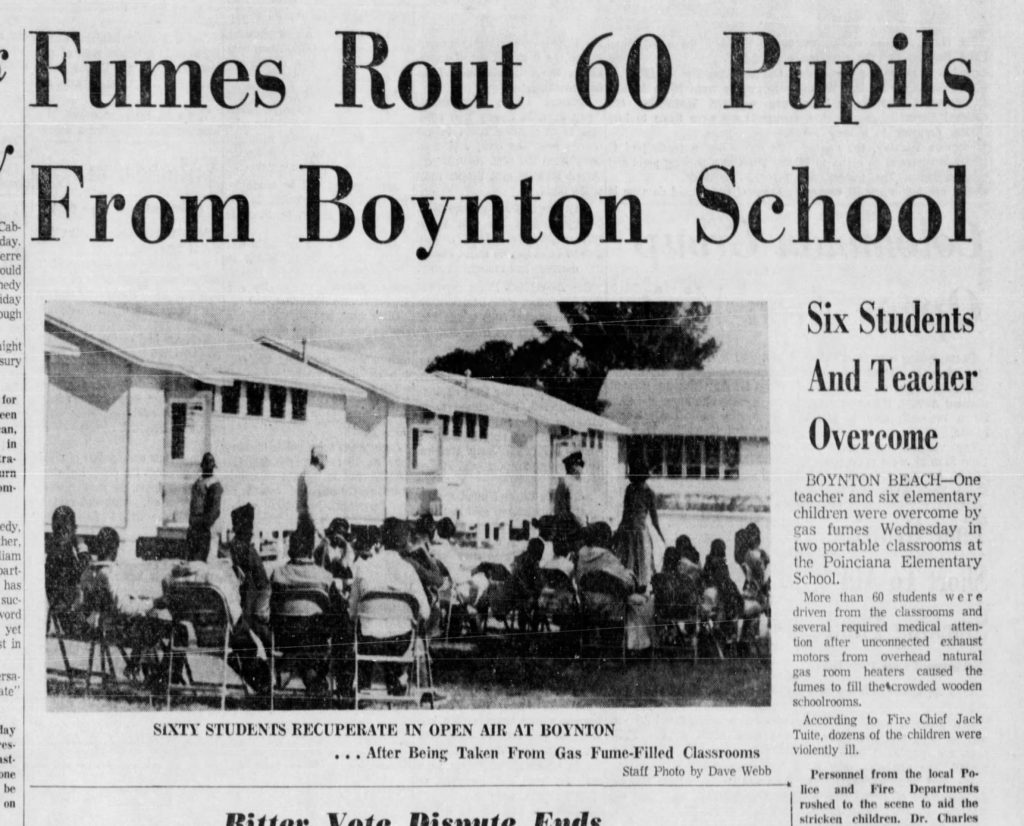

JOHN ASHLEY CAMP DISCOVERED IN WESTERN BOYNTON

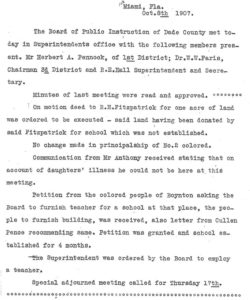

According to Marvin Pope “Ham” Anthony in a Historical Society of Palm Beach County oral history interview with Harvey E. Oyer III, Joe Ashley (John Ashley’s father) and one of John’s brothers both worked at the Anthony’s Store in the men’s wear department around this time. Anthony’s father was friends with both the Ashley and Mobley families and claimed that they were good, outstanding people. John Ashley was really the only bad one. The Mobleys lived on Tanglewood Court in West Palm Beach.

Anthony related a surprising story about Boynton’s Chuck Pierce [Charles W. Pierce, Jr.] who worked in the sporting goods department at Anthony’s, who was given a pistol for Christmas. Pierce and a friend were “out back of Boynton where their home was.” Pierce told Anthony that while out in the woods the two boys met a nice-looking man who inquired what they were doing. When they said they were just turkey hunting, the man offered to do it for them and asked for the gun. After a long time, they finally heard a shot, and the fellow gave them a turkey and the gun back. The Ashley Gang robbed the Bank of Boynton a few weeks later. As the story goes, one of the boys went up to see what the handcuffed thugs looked like “…and this nice-looking man looked over and winked at him and said ‘Son, how was that turkey?’” Apparently Chuck Pierce had loaned his new pistol to the bandit John Ashley.

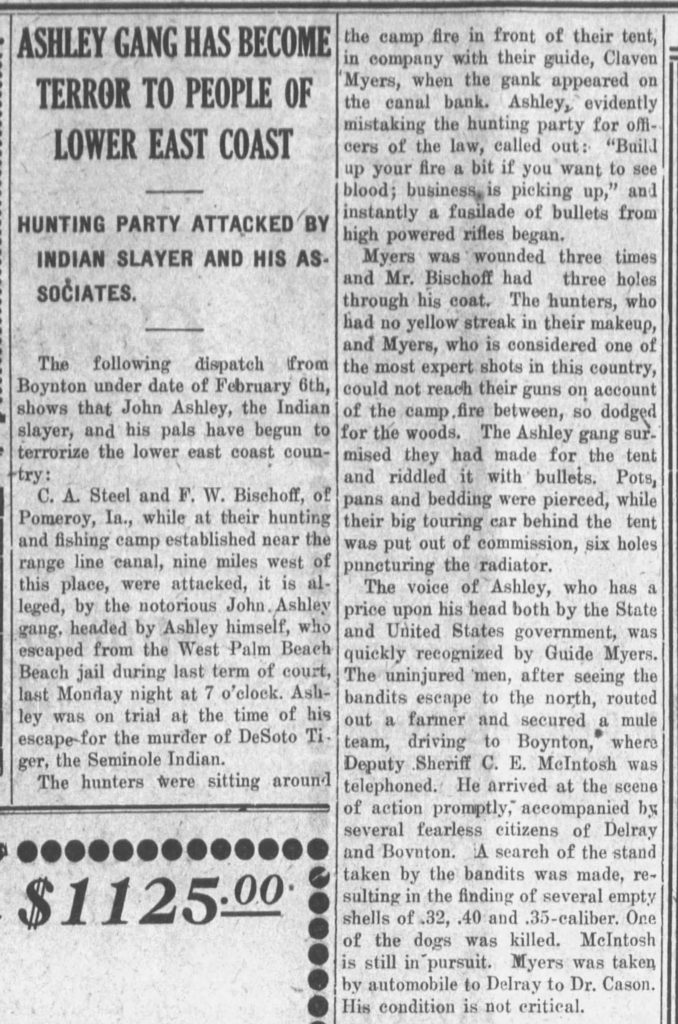

Boynton hunting party attacked by Ashley Gang 19 Feb 1915, Orlando Evening Star)

1915 February

John Ashley and his band of thugs terrorized and machine-gunned a hunting party camped out west of Boynton near the Rangeline (State Road 441).

(19 Feb 1915, Orlando Evening Star)

1914 November

JAIL BREAK

John Ashley breaks out of jail.

1915 – February

BLUNDERING BANDITS

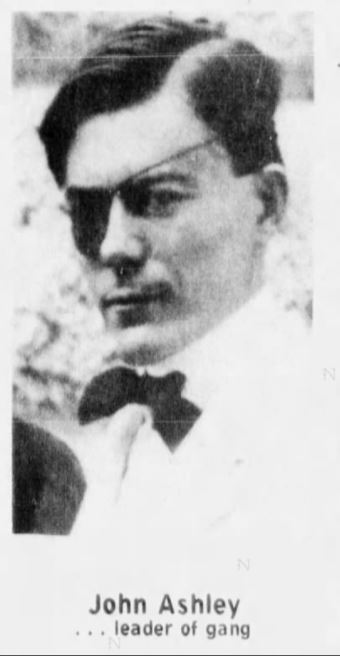

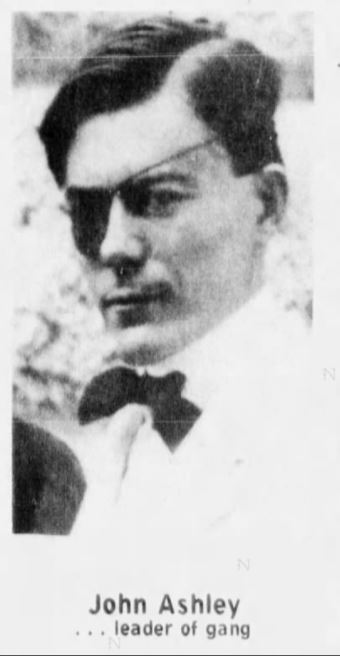

The Ashley Gang robs the Stuart Bank. John Ashley loses his right eye when his accomplice accidentally shoots him. Since Ashley’s wound demanded medical attention, the fugitive was apprehended.

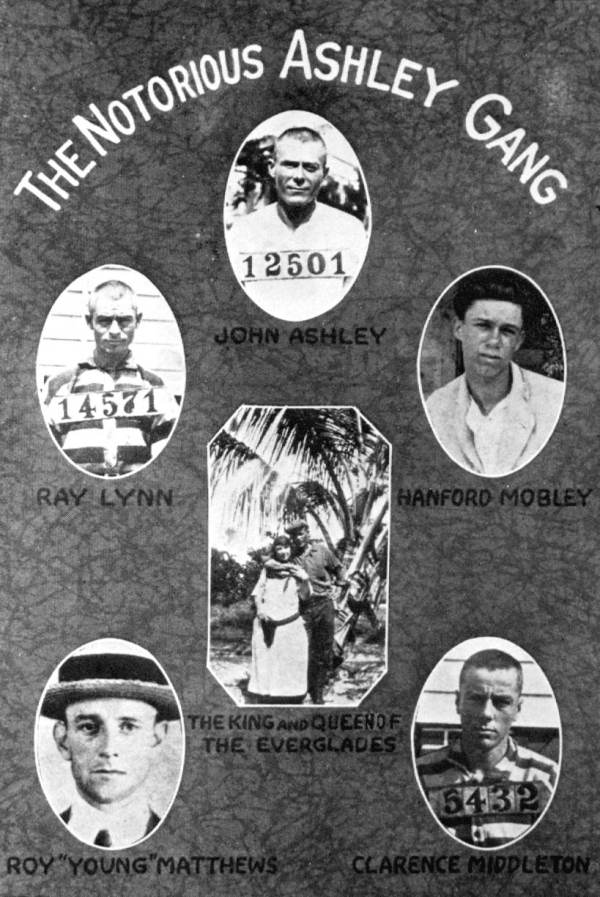

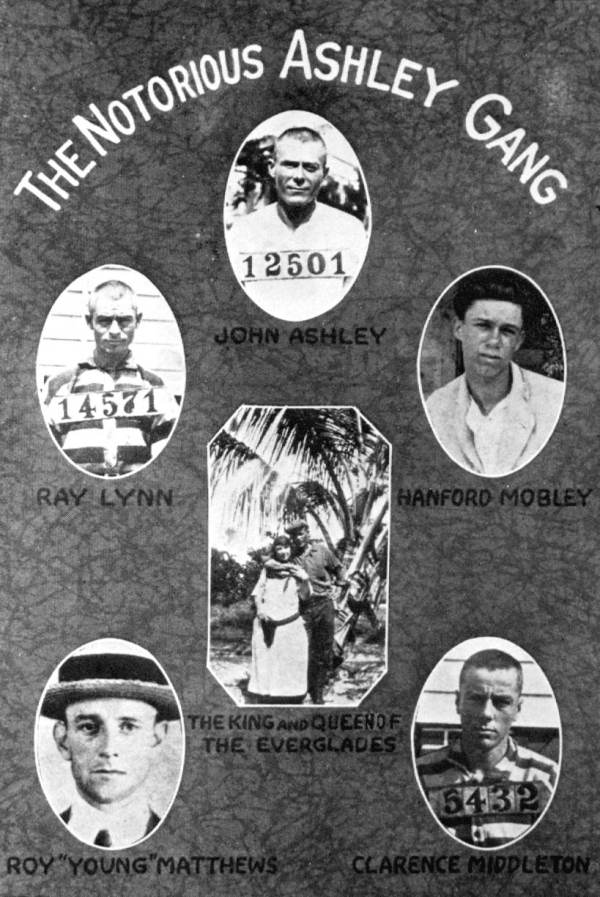

John Ashley, leader of gang

1915 – February

30 local men form a posse to hunt down the “organized crime family” that had no respect for the law. Sheriff Baker wanted them “dead or alive.”

1915 March

Ashley is captured and imprisoned in the Miami jail.

1915 June

Bob Ashley (John’s brother) ambushes and kills Miami Police Department Deputy Sheriff Wilber W. Hendrickson in an attempt to release John Ashley. In the process, Bob Ashley and another police officer, John Rhinehart “Bob” Riblet are killed. (Sheriff Hendrickson was a great uncle of Boynton resident Jean Ann Thurber and brother to her grandfather.)

Miami Deputy Sheriff – Wilber Hendrickson

Photo shown below: (L-R) Alvin Hendrickson and Captain U.D. Hendrickson (uncles of Wilbur Sr.), Dorothy Hendrickson, Etta Hendrickson, and Frances Lane Hendrickson Bridgeman (Etta was U.D.’s wife and the mother of Dorothy and Frances), Marion Platt Hendrickson, Wilbur W. Hendrickson Sr. and Wilbur W. Hendrickson Jr. (Jean Ann Thurber Photo)

Hendrickson Family, courtesy Jean Ann Thurber

1916

John Ashley sentenced to 17 ½ years for the Stuart Bank heist. Ashley is finally sent to prison. Two years later he escaped from a road gang. John Ashley is once again a fugitive from the law.

1920

The early Boynton Bank was a repeat victim. “Ashley’s here!” Tellers would fill up their bags; no alarms or dye packs at that time. The notorious outlaws rob banks across Florida including Fort Meade, Avon Park, Pompano Beach, and Stuart.

1921

Horace Bentley Murray, Billy Smith’s brother-in-law, is elected Boynton mayor.

Horace Bentley Murray

Hanford Mobley, Ashley Gang Leader (Florida Photographic Collection)

1922 May

The Ashley gang (ordered by John while he was still in jail) made their second robbery of the Stuart Bank. Hanford Mobley, (John Ashley’s nephew and brother of Dorothy Smith Mobley’s husband Lubby) assumed leadership of the gang. The handsome teenager held up the bank dressed as a woman and fled with $8,000.

A posse of men from the sheriff’s office chased them for 265 miles and deputy Sheriff Morris R. Johns dropped dead from indigestion two days after the unsuccessful hunt.

Members of the notorious Ashley Gang

1924 February

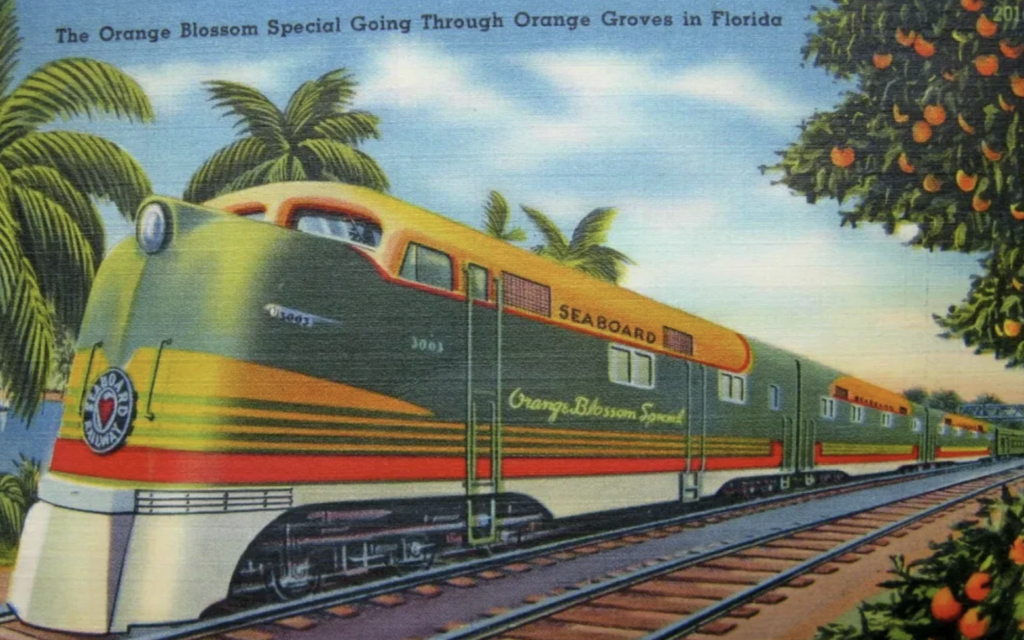

Hanford Mobley robbed the Florida East Coast Railway train.

1924 September

The Mobley-Ashley gang robbed the Pompano Bank of $9,000.

1924 November

DAY OF RECKONING

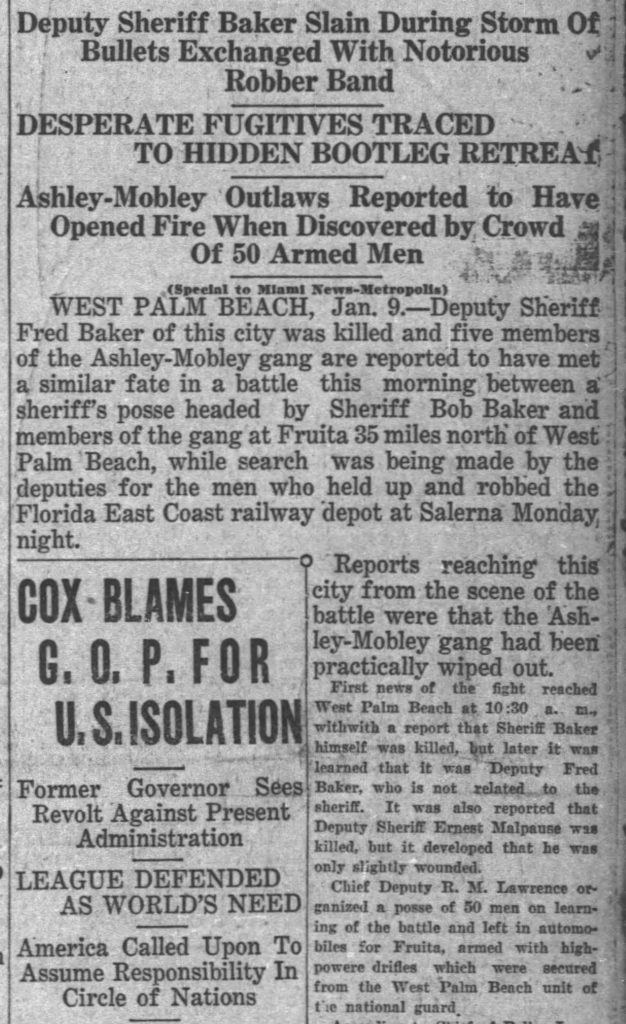

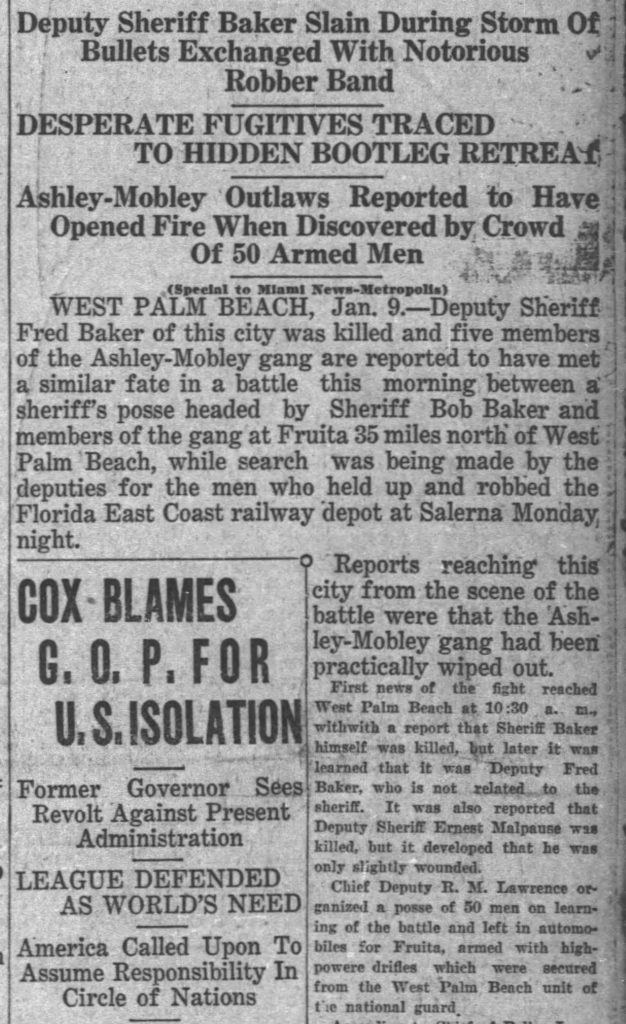

Deputy Frederick A. Baker led a posse of over 50 men to the Ashley/Mobley camp. Some were equipped with guns borrowed from the old National Guard armory. As the posse entered the camp, the fugitives opened fire. Deputy Baker and Joe Ashley were killed in the shootout. Laura Upthegrove was wounded, but escaped. The remaining fugitives hid in the Everglades as their hideout was burned to the ground.

Deputy Fred Baker and Joe Ashley Killed (8 Jan 1924 The Lake Worth Herald)

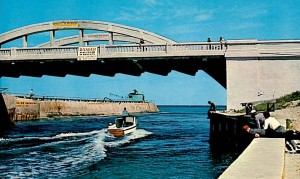

In a carefully orchestrated trap on the Sebastian bridge, four additional members of the Mobley-Ashley gang were shot and killed along with Deputy Sheriff Fred Baker. The four outlaws were John Ashley, nephew Hanford Mobley, Ray Lynn and Clarence Middleton. The Palm Beach Post reported that the slaying of Ashley gang brings end to career of crime.

Deputy Fred Baker killed by Ashley-Mobley Gang (9 Jan 1924, The Miami News).

1927

Laura Upthegrove dies after drinking a bottle of disinfectant. The “Queen of the Everglades” is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in West Palm Beach, in an unmarked grave.

1929 – January

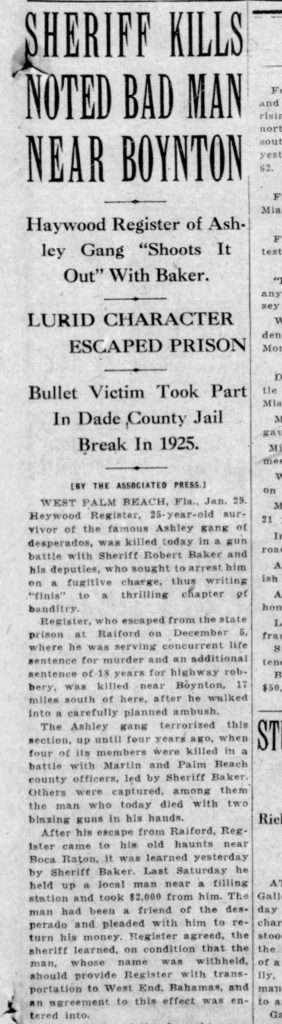

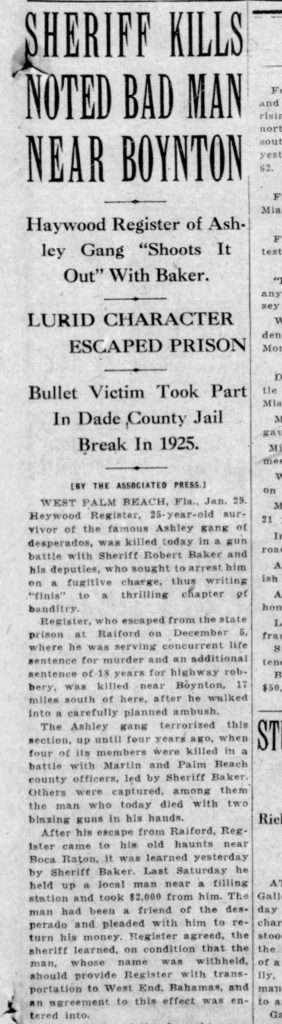

Prison escapee Haywood Register, Ashley Gang leader killed in shootout with Sheriff Baker in Boynton (30 Jan 1929, The Miami Herald)

Haywood Register, the assumed Mobley/Ashley Gang leader who was sentenced to life in the Florida State Prison, escaped and was gunned down along the canal in Boynton by Sheriff Bob Baker. Years later, several Boyntonites described witnessing this event.

1930

Lubby Mosley arrested and jailed on an illegal liquor distribution charge at a moonshine camp.

1933 – February

Sheriff Robert Baker (son of George Baker) died, and the newspaper reported that he died “with his boots on.” William Hiram “Hy” Lawrence, appointed after Baker’s death is another Boynton connection. Lawrence and his brother Red owned Boynton property in the vicinity of today’s Lawrence Road, which is named after them.

Sheriff Robert C. “Bob” Baker of Palm Beach County (24 Feb 1933, The Miami Herald).

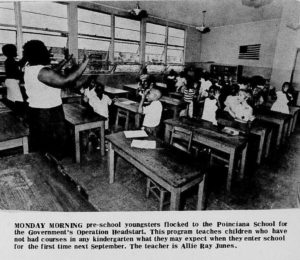

1973

Boynton resident Sam Adams called a local Boynton Beach newspaper, The Examiner, and told publisher Vernon Lamme that although the Mobley-Ashley gang hid out in Boynton and even robbed the bank that John Ashley was a kindly soul and to remember him as a kind of “Robin Hood.”

1973

Actors from Little Laura & Big John (1973)

Movie based loosely on the Ashley Gang produced. It is called “Little Laura and Big John.” Reviews are not good.

1980

Glenn Murray, in his 1980 oral history interview, denied claims that he, as a teenager, supplied the Mobley-Ashley gang members with groceries.

1986

Vandals desecrate and loot the Native American Glades people ceremonial mounds north of Boynton Beach Boulevard and west of 441, looking for the legendary treasure stashed by the Ashley gang.

1992

Boynton resident Arris “Ozzie” Lunsford claimed in a 1992 oral history interview that he witnessed the the Palm Beach County sheriff’s office shoot-up with the getaway car. Lunsford was born in 1909, and moved to Boynton at age 14 or 15 (accounts vary). He describes fishing along the Boynton canal and witnessing the sheriff shooting up the Ashley Gang bandit and that he saw him inside the trunk of the car. This account coincides with the January 1929 capture of fugitive Haywood Register.

2021

As we researched this story, we reached out to some Murray family descendants. Ted Murray remembers stories that his great-grandmother Mary Smith Murray was a crack shot, shooting quail and other game. He owns her .38 pistol. He had no recollection of the family’s relationship to the Mobley-Ashley gang, but he wasn’t surprised.

EPILOGUE

What happened to Dorothy Smith Mosley?

Dorothy divorced Lubby Mosley in the 1930s; she married Robert Garner, a mechanic. She is shown on the 1940 Census as living with her parents, husband, and child. The record showed that she had a 4th grade education.

What happened to Lubby Mosley?

Lubby continued his life of crime and was in and out of jail the rest of his life.

What happened to “Uncle Billy” Smith?

Smith, Martin County’s Superintendent of Roads, ironically perished in a head-on automobile collision in 1951 with his daughter Dorothy at the wheel. Newspaper accounts state that the car’s “brakes failed.”

REFERENCES

Lake Worth Herald

Miami Metropolis

Miami News

Palm Beach Post

Sheriff Bob Baker v. the Notorious Ashley Gang

The Ashley Gang – Palm Beach County History Online

The Ashley Gang Landmarks

HISTORICAL VIGNETTES: Guess who took outlaw John Ashley’s glass eye as a key fob memento?

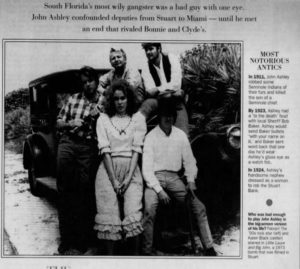

South Florida’s Most Wiley Gangster

The Ashley Gang and Frontier Justice

Florida Outlaws: Move over Bonnie and Clyde

Desperados: The Life and Times of John Ashley

The Notorious Ashley Gang by Sally Ling