1st Permanent Schoolhouse in Boynton, ca. 1907

It is hard to imagine a Boynton Beach without a schoolhouse. In 1895, only a handful of people lived here, and for most of those, formal education was unnecessary. Between 1900 and 1910, the little settlement, known simply as Boynton, grew in population from less than 100 people to nearly 700.

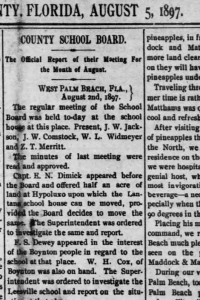

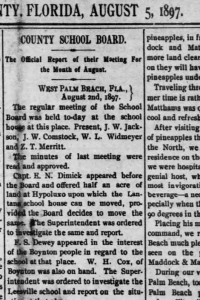

Though they had no children of their own, Fred and Byrd Spilman Dewey recognized the need for a school in the growing settlement of Boynton. In 1897, Fred S. Dewey appeared before the school board and petitioned for a Boynton school, as reported in the August 5, 1897 Tropical Sun. A small, one-room schoolhouse on stilts was erected on land donated by the Deweys, in the area of the present day Dewey Park (Ocean Avenue and NE 4th Street). Miss Maude Gee was the first teacher, referred to in the Tropical Sun as Boynton’s “Instructoress.” A makeshift school for African-Americans; known at that time as a “Colored School” opened in 1896 in the area of today’s Poinciana School.

Article from Tropical Sun

Albert P. Sawyer donated the land for the first permanent schoolhouse for White children, from his Sawyer’s Addition to the Dewey’s original Town of Boynton plat on November 29, 1902. In 1904 the two-room wooden school which was located near present-day Ocean Avenue and Seacrest Blvd. (then Green Street) opened with W.S. Shepard as Principal and Agnes Halseth as teacher. A few years later, in 1909, Palm Beach County was carved out of Dade County.

The Boynton School, ca. 1913

In 1912, the Palm Beach County School Board approved a contract with A. Mellson to construct the first part of a new school building. The original plan left the upstairs unfinished and did not include the fire escape. The Board approved a contract for William W. Maughlin, an architect from Baltimore to design a new masonry vernacular school. Maughlin, born in 1847, had previously designed the Palm Beach High School in 1908-1909 and was a draftsman for the Florida East Coast Hotels. Maughlin and his firm of Ruggles and Weller constructed the schoolhouse. The Boynton School was Maughlin’s last project, he passed away suddenly in October 1913 at his office and is buried in Woodland Cemetery.

Architect Wm. Maughlin’s Woodmen of the World Monument (1847-1913) at Woodlawn Cemetery.

In December, 1912, the Board of Instruction authorized work to be completed on the two-story, six classroom building. The structure, one of the first in Boynton to feature indoor plumbing, had a signature portico, large sash windows and transom windows to facilitate the flow of sunlight and fresh air. The floors were made from Dade County Pine, and walls affixed with bead board.

The sturdy school featured a new system in masonry, known as Dunn Tile. The molds, designed by the W.E. Dunn Mfg. Co. of Chicago, the largest manufacturer to make concrete block forms, transformed the building industry. The Dunn Co. used a revolutionary concrete and plaster mixer to make concrete for block, a precursor to the concrete block house.

Miss Annie Streater (Shepard) with her 1st to 4th grade pupils, ca. 1913

The school opened September 8, 1913 for grades 1-12 with 81 students in attendance. Little Glenn Murray, age three, was hastily added to the list of pupils so the school had adequate students for the staff of three teachers and a principal. Miss Annie Streater taught the first year and Howard Frederick Pfahl, a native of Cleveland, Ohio, served as school principal for the years 1914-1915. Pfahl motored to school on an Indian motorcycle.

Principal Howard Phahl, ca. 1915.

The Boynton School served grades 1 -12 until 1927, when the Boynton High School opened next door. For the next three decades the building served as a traditional 1-8 grade school, until Boynton Jr. High opened in 1958. The structure served as a school for primary grades and elementary students until its closing in 1990.